Einstein–Infeld–Hoffmann equations

The Einstein–Infeld–Hoffmann equations of motion, jointly derived by Albert Einstein, Leopold Infeld and Banesh Hoffmann, are the differential equations of motion describing the approximate dynamics of a system of point-like masses due to their mutual gravitational interactions, including general relativistic effects. It uses a first-order post-Newtonian expansion and thus is valid in the limit where the velocities of the bodies are small compared to the speed of light and where the gravitational fields affecting them are correspondingly weak.

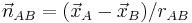

Given a system of N bodies, labelled by indices A = 1, ..., N, the barycentric acceleration vector of body A is given by:

where:

is the barycentric position vector of body A

is the barycentric position vector of body A is the barycentric velocity vector of body A

is the barycentric velocity vector of body A is the barycentric acceleration vector of body A

is the barycentric acceleration vector of body A is the coordinate distance between bodies A and B

is the coordinate distance between bodies A and B is the unit vector pointing from body B to body A

is the unit vector pointing from body B to body A is the mass of body A.

is the mass of body A. is the speed of light

is the speed of light is the gravitational constant.

is the gravitational constant.

The coordinates used here are harmonic. The first term on the right hand side is the Newtonian gravitational acceleration at A; in the limit as c → ∞, one recovers Newton's law of motion.

The acceleration of a particular body depends on the accelerations of all the other bodies. Since the quantity on the left hand side also appears in the right hand side, this system of equations must be solved iteratively. In practice, using the Newtonian acceleration instead of the true acceleration provides sufficient accuracy.[1]

References

- ^ Standish, Williams. Orbital Ephemerides of the Sun, Moon, and Planets, Pg 4. http://iau-comm4.jpl.nasa.gov/XSChap8.pdf

- Original paper [1]

- Kovalevsky, Seidelmann (2004). Fundamentals of Astrometry, Pg 173

![\begin{align}

\vec{a}_A & = \sum_{B \not = A} \frac{G m_B \vec{n}_{BA}}{r_{AB}^2} \\

& {} \quad{} %2B \frac{1}{c^2} \sum_{B \not = A}

\frac{G m_B \vec{n}_{BA}}{r_{AB}^2}

\left[ v_A^2%2B2v_B^2 - 4( \vec{v}_A \cdot \vec{v}_B) - \frac{3}{2} ( \vec{n}_{AB} \cdot \vec{v}_B)^2 \right. \\

& {} \qquad {} \left. {} -

4 \sum_{C \not = A} \frac{G m_C}{r_{AC}} -

\sum_{C \not = B} \frac{G m_C}{r_{BC}} %2B \frac{1}{2}( (\vec{x}_B-\vec{x}_A) \cdot \vec{a}_B ) \right] \\

& {}\quad{} %2B \frac{1}{c^2} \sum_{B \not = A} \frac{G m_B}{r_{AB}^2}\left[\vec{n}_{AB}\cdot(4\vec{v}_A-3\vec{v}_B)\right](\vec{v}_A-\vec{v}_B) \\

& {} \quad {} %2B \frac{7}{2c^2} \sum_{B \not = A}{ \frac{G m_B \vec{a}_B }{r_{AB}}}

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/96cf7f1cab0b39e8f622cc2deb0f7b94.png)